The Sweet Taste of Success

Interview with Shawn Askinosie

Lawyer-turned-chocolate maker Shawn Askinosie, founder of the direct-trade, high-end chocolate company Askinosie Chocolate and author of Meaningful Work, advocates for a radically different entrepreneurial mindset and purpose.

Why did you decide to start a chocolate business?

I was a criminal defense lawyer for nearly twenty years and was ready for a change; I just didn’t know what it was going to be. I spent five years searching for my next inspiration. I didn’t have any hobbies; I spent most of my time either preparing for the courtroom or in the courtroom. I loved it but then stopped loving it. I didn’t have a lifelong love of chocolate, but I gradually started making chocolate desserts and then got the spark to make chocolate from the bean.

Such discover of one’s passion is a more prevalent mindset today. In the past few years, millions of people have quit their jobs to find fulfillment rather than just jumping to the next shiny object that came into their purview.

Can pursuing “shiny objects” be detrimental to entrepreneurs?

It can destroy a business if you’re not vigilant because if you don’t have the cash flow and capital to do it, the business strays off its mission, which is called mission creep. It’s especially dangerous during these times of raging inflation and looming recession. I think that businesses need to be very careful how they navigate the difference between the shiny object they think will bring them to the promised land and what their business actually needs. After all, fish are hooked by shiny objects.

As your dad did, you frequent a monastery. Tell us about that:

I started going on retreats to Assumption Abbey twenty-two years ago for the silence and solitude. It’s a Trappist monastery where my dad spent a lot of time, and it’s where he spent his last night before he died.

The abbey’s biggest influence on me is concerning sufficiency. It’s how the monks live their lives: they make something they can sell but only enough to survive, and this idea has found its way through all aspects of my life and business. As entrepreneurs, asking ourselves “How much is enough?” can be a real challenge—but a rewarding one.

How smooth was your transition from high-paid lawyer to chocolate-making novice?

As a lawyer, I was at the top of my career, so I had a naive, nothing-can-hurt-me mindset—even though I put our life savings into this venture. I felt confident because I figured I could always practice law again. That said, I took zero business classes in college, didn’t know how to make food, and am not that mechanically inclined, so I had to get help. To this day, people are teaching me.

I also readjusted my definition of financial success. I understood from the beginning that I was going to make less money, which relates to sufficiency economy. I didn’t set out to create the biggest, fastest-growing company possible. Instead, I envisioned that it would be small and that I’d view success through moments of transcendence.

Vocation—a quest to discover your true self and life purpose—is a central topic in your book. Would you explain how it can help a company?

I think that finding a vocation is especially important for organization founders. In the beginning, they must step away and find a place of solitude—not necessarily a monastery—to discover what their personal vocation is. You’re certainly not going to find it by googling it, and it takes time; it took me five years to start Askinosie Chocolate. Plus, for entrepreneurs, especially of startups, there’s usually no distinction between their personal life and business life; it’s almost inevitable that the two get infused into the business. Then, ideally, that vocation is inspirational for your employees. Before you know it, you have people all pulling in the same direction and have a company vocation.

Another concept discussed in Meaningful Work is mutuality. What does that mean to your business, your employees, and your farmers?

Father Greg Boyle, a Jesuit priest who has worked with gang members in Los Angeles for thirty-five years, wrote about it: having enough humility to truly connect with people and lose any sense of hierarchy or labels. It’s being, as opposed to doing. Admittedly, this may be very hard for entrepreneurs because we pride ourselves on discovering solutions to problems. That’s literally what I did as a lawyer.

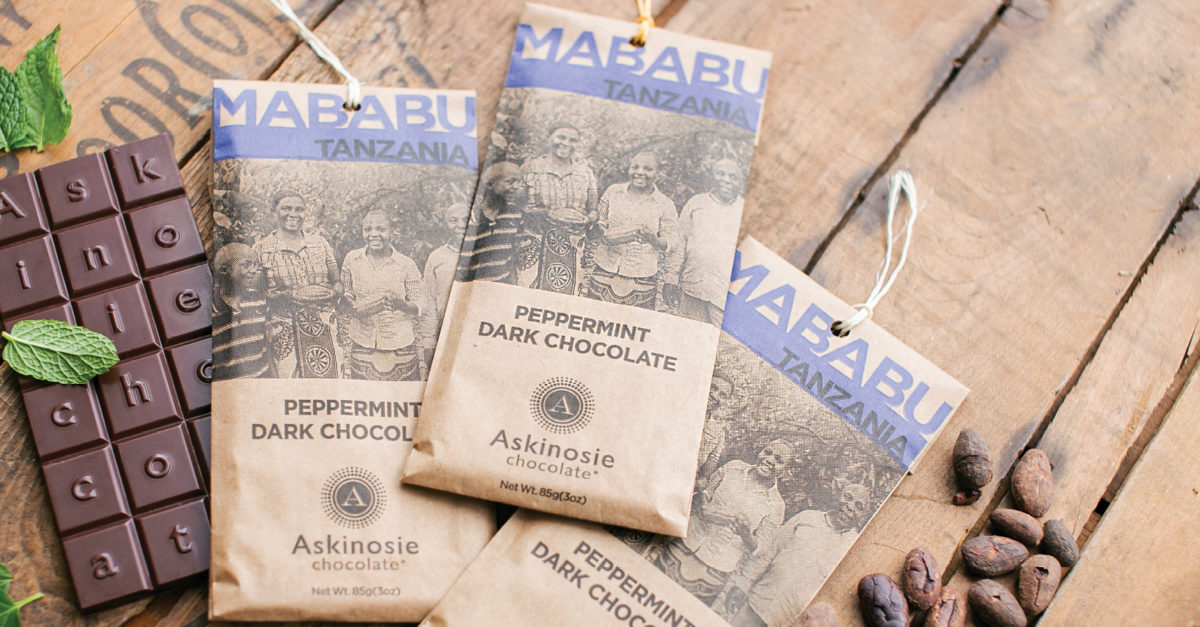

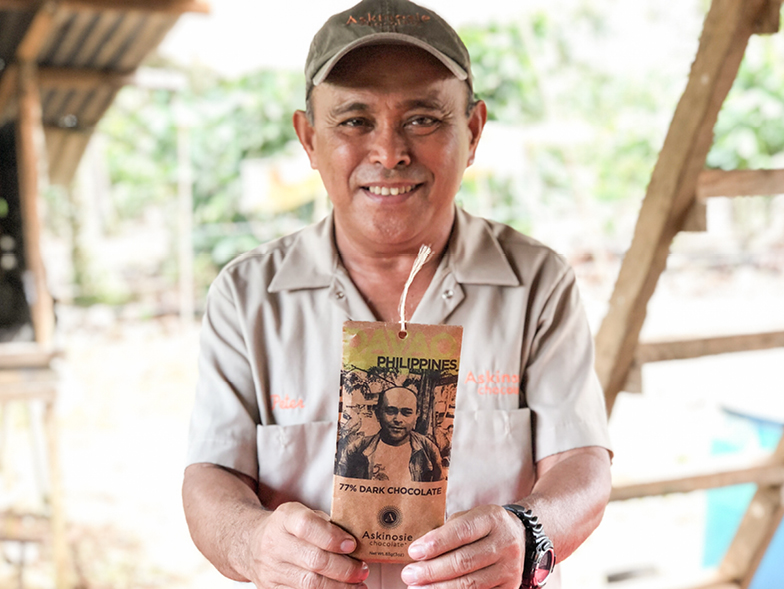

My best example of mutuality would be our farmer relationships. Since I started the business, I’ve been buying and importing cocoa beans directly from our farmers in Davao, Philippines; Zamora, Amazonia; Del Tambo, Ecuador; and Mababu, Tanzania. But I also work with them on a variety of community-development projects. Mutuality requires not saying, “Step aside; we’ll handle this.” That is the traditional approach. Quite honestly, in many ways, it is an easier one, but it’s not ours because the farmers are our partners and friends. It’s a back and forth between me and the farmer, and neither is above the other as the solution provider. The same applies to our employees. Ultimately, mutuality makes our chocolate better.

You believe that greatness and goodness are inextricably intertwined. How?

I love the way Kahlil Gibran sums it up: “If you bake bread with indifference, you bake a bitter bread that feeds but half man’s hunger.” So we don’t do our work half-heartedly or skew it only to the bottom line. We want to make our chocolate with the utmost care and respect—and we believe that this ultimately gives us a better product and improves our lives.

That said, I understand a bottom-line perspective, and I think that there’s a place for businesses that prioritize it. Personally, though, I don’t want to go through life missing out on opportunities to experience much more. Sure, I have a financial meeting every week, so I’m looking at cash flow, forecasts, sales plans, and budgets. But I’m designing opportunities into them to keep me connected to why I started the business in the first place, and traveling to meet with our farmers is a big part of that. Sixteen years and forty-five trips later, I’m getting even more out of it now than I did on my first trip.

How do you foster transparency in your business?

We practice direct trade, which is all about relationships and trust. With our farmers, we have a very clear set of criteria and specifications as to what we need in cocoa beans and how we conduct business. In turn, we profit share with them, and we pay them directly. From the beginning, we’ve also put all our financials on our website so our customers know exactly how we spend our money. And we open our books weekly to our employees so that everybody knows where we are financially. This creates a sense of peace for them, especially in times of trouble, that everything is OK at the company.

Does the title of your book resonate today more than ever?

When we started sixteen years ago, some companies were mindful of their community, whether that meant their street, city, country, or world. More companies claim to practice it today. The difference is that consumers, especially younger people, are looking for meaning in what they do and what they buy, so they’re combatting marketing strategies with ever-increasing levels of discernment. They have very sensitive BS detectors, so they easily see through a ruse and expect companies to do what they say they do.

You de-emphasize company scaling. Why?

Western culture has conditioned us to believe that growing or scaling businesses is the de facto model—and for good reasons, such as employing more people, bettering communities, and getting better returns for investors. All that may be true, but I challenge whether entrepreneurs can stay tethered to their personal and company vocations. That’s what I mean by practicing reverse scale—I want my company to grow deep, not wide. It’s why I still go to our farmer locations and why we have only twenty-two employees.

When it comes to vaccine distribution or hunger or disaster relief, people don’t need reverse scale; they need scale. But entrepreneurs can use reverse scale to transform themselves in a way that can help change the world. I don’t know if it’s going to come back tenfold for me, and I don’t care because it’s not quid pro quo. That’s why I believe reverse scale has a lot of power.

What’s the meaning behind your motto “It’s not about the chocolate; it’s about the chocolate,” and how has it contributed to your success?

I have a timely example to explain it. We just won a sofi Award from the Specialty Food Association. It’s an international contest, and the competition is stiff. I am laser-focused on making sure that our chocolate is of the highest quality so we can win such awards. I don’t want people to buy our chocolate because of all the things we’ve been talking about—I want them to buy it because it tastes great and they love the quality.

If they get to know us and like our story, awesome. However, I could make a chocolate bar that tastes like sawdust, and they would probably try it based on the story and purpose behind it. But they wouldn’t buy it again or share it with their friends. If they didn’t, then we couldn’t provide for our employees and farmers as we do; and without working directly and having relationships with our farmers, we wouldn’t have the premium cocoa beans for our products and couldn’t produce such high-quality chocolate. Therefore, it’s not about the chocolate; it’s about the chocolate. And it’s how we’ve remained competitive all these years: by being focused on quality and it being inseparable from our vocation of mutuality and creating meaningful, fulfilling work.

For more info, visit askinosie.com